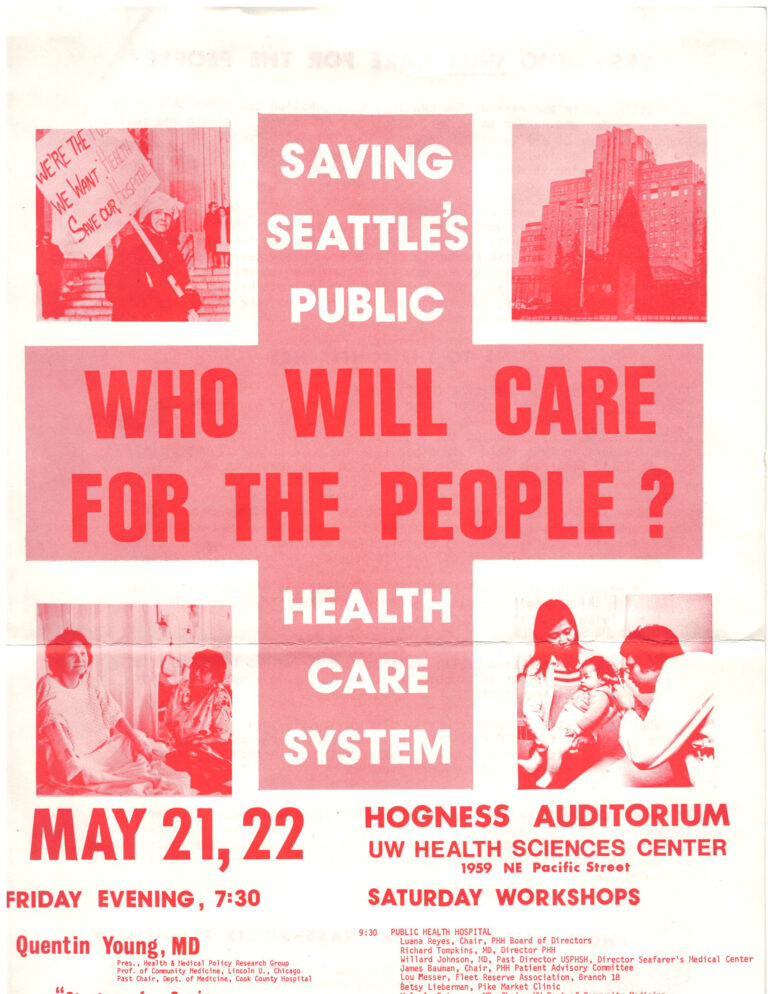

OUR HISTORY

A History of the Pacific Tower Campus

The early founders, and subsequent leaders, of this campus understood its immense value as a public benefit. Decades have seen multiple iterations of campus uses – a hospital, a site for primary care, a high-tech headquarters, an office building – and today a source of grant funds to support health equity.

These adaptations, through highs and lows, all enabled the Campus to remain true to its north star: being a champion for the people in our community who lack access to effective healthcare. While this north star won’t change, the pathway we follow will.